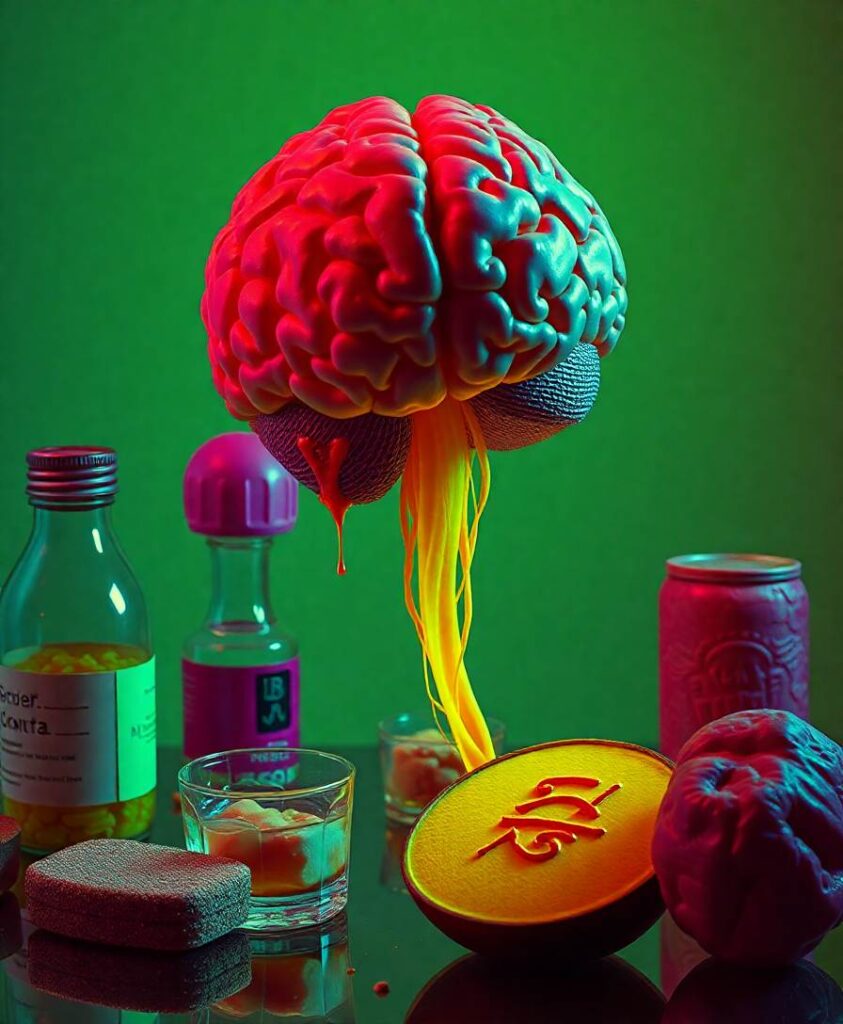

The team found that short-term clearance of amyloid does not quickly restore the brain’s waste-removal pathways. This suggests that damage to neurons and disruptions in how the brain clears proteins and debris may begin earlier than we can detect and may become entrenched. For people living with Alzheimer’s or caring for them, the result means treatments will likely need to do more than remove a single hallmark of the disease.

Understanding how different repair systems in the brain interact matters for anyone interested in healthier aging and inclusive care. If you want to know which pathways might need support alongside amyloid-targeting drugs, and how this shapes the next wave of therapies aimed at preserving memory and independence, the full study connects those clinical findings to the bigger question of restoring human potential after neurodegeneration.

Japanese researchers found that lecanemab, an amyloid-clearing drug for Alzheimer’s, does not improve the brain’s waste clearance system in the short term. This implies that nerve damage and impaired clearance occur early and are difficult to reverse. Their findings underscore that tackling amyloid alone may not be enough to restore brain function, urging a broader approach to treatment.