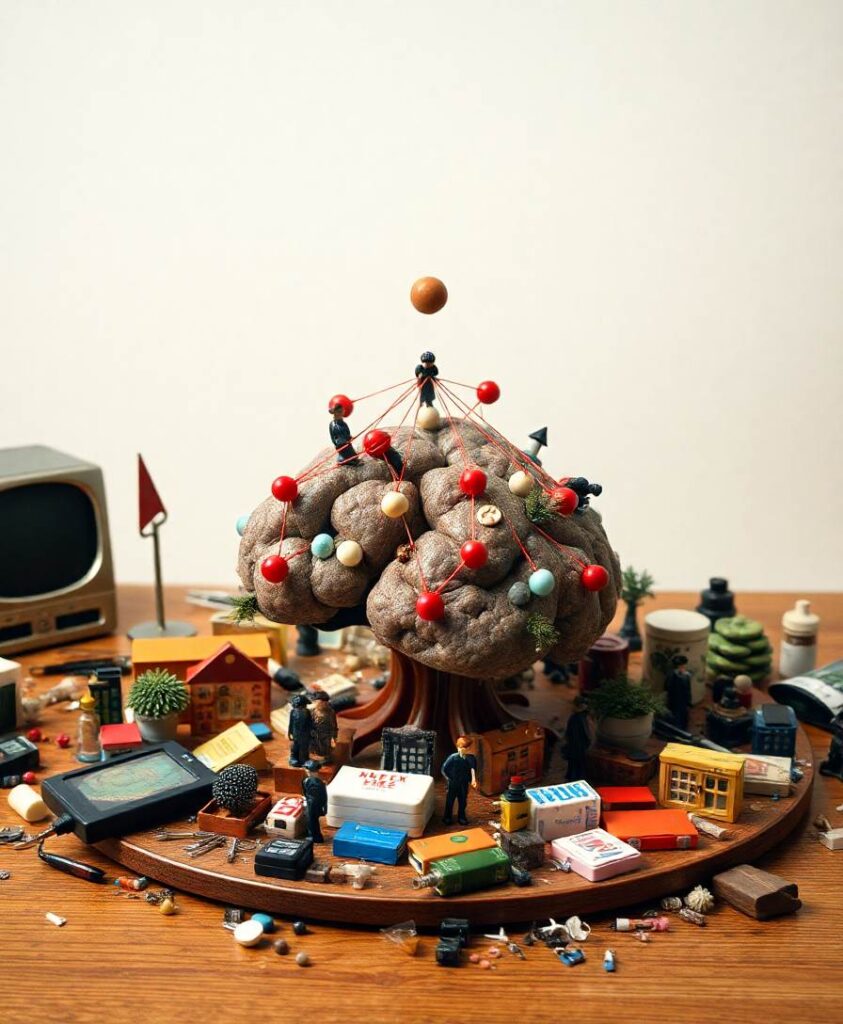

Memory and spatial orientation are deeply interconnected, forming the foundation of our daily interactions with the environment. When our brain’s navigation mechanisms start to falter, it can feel like losing a fundamental part of ourselves. The Stanford study highlights not only the vulnerabilities of our cognitive mapping system but also the remarkable potential for individual resilience against age-related decline.

What makes some minds more resistant to cognitive aging? The research points to intriguing genetic variations that could protect certain individuals from spatial memory deterioration. This discovery opens up exciting possibilities for understanding brain plasticity and potentially developing strategies to maintain cognitive sharpness. For anyone curious about how our brains adapt, change, and sometimes defy expected patterns of aging, this research offers a window into the extraordinary complexity of human potential.

Stanford scientists found that aging disrupts the brain’s internal navigation system in mice, mirroring spatial memory decline in humans. Older mice struggled to recall familiar locations, while a few “super-agers” retained youthful brain patterns. Genetic clues suggest some animals, and people, may be naturally resistant to cognitive aging. The discovery could pave the way for preventing memory loss in old age.