The study used a long-term design in aging rats to track changes that unfold slowly, and that slow unfolding is precisely why the question feels urgent. Small experimental groups and animal models do not map perfectly onto human lives, yet they let scientists test mechanisms in controlled ways. That method helps us think about pathways—from stress hormones to inflammation to neural connections—that could link social conditions to cognition in people across the lifespan.

Understanding these pathways matters for how communities support aging, learning, and inclusion. If social environments influence the biology of aging brains, interventions could move beyond lists of activities and toward designing everyday social structures that sustain connection. Follow the link to read how the researchers probed this problem and to consider what their findings might mean for human potential, caregiving, and fair access to healthy aging.

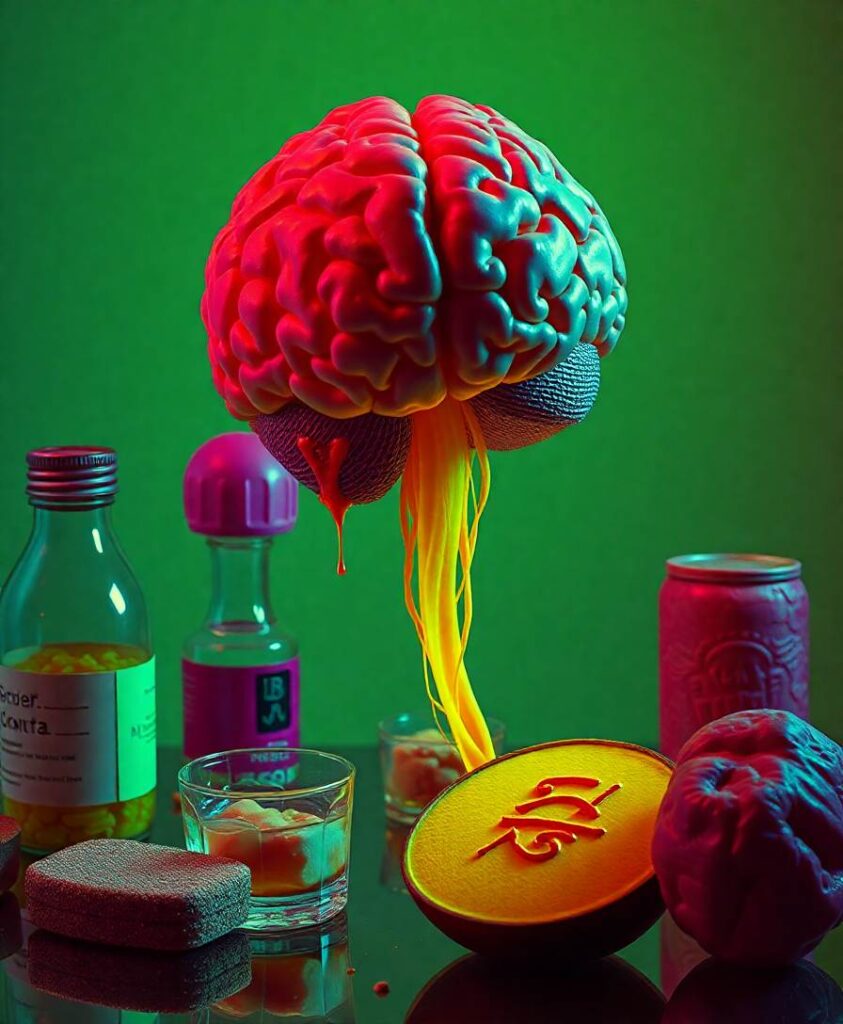

A new study on rats conducted by researchers at the University of Florida and Providence College found that living alone acted like a toxin in their aging brains, speeding up cognitive decline. The study involved 19 rats divided into two groups and tracked over 26 months -…